윤동천

M’VOID is a program that plans and presents exhibitions of leading artists at home and abroad who question contemporary aesthetic values while strengthening their works with insights.

ABOUT

작가노트

일반 사람들은 대개 ‘추상’하면 거리감을 느낀다. 우리 주변을 구성하고 있는 무수한 요소들이 이미 추상임에도, 그림으로서의 추상과 일상에서 마주하는 추상을 전혀 다르게 대하고, 다르게 느낀다. 예를 들면 저녁노을을 보고는 아름답다고 느끼는데 노을만을 그린 그림을 보고는 추상은 잘 모르겠다고 한다. 이는 한편 현대미술의 죄과이기도 하다.

이번 전시에서는 추상에 다다르는, 혹은 도출되는 여러 경로를 통해 추상에 대한 이해를 돕고자 한다. 이는 학습을 위해서가 아니라 누구나 자신의 미감을 스스로 존중하기를 바라는 마음에서다. 결국 추상도 별게 아니라는 생각을 하게 된다면 좋겠다. 그림의 궁극 목표는 개개인 누구나가 주체적 인간으로 살아가는데 이바지하는 것이다.

윤동천의 형식주의

신정훈(미술평론/서울대학교 미술대학 교수)

‘형식주의’는 윤동천의 미술에 어울리지 않는, 더 나아가 도발적인 용어일 것이다. 그가 이를 언급하거나 내세운 바 없고 오히려 자신의 미술은 형식이나 조형이 아니라 의미를 전하고 나누기 위한 것임을 강조해왔기 때문이다. 그에 따르면 주제는 자신의 문제, 미술의 문제, 그리고 우리 사회의 문제로서, 이들은 주체, 작가, 시민으로서 그가 말할 수 있는 최소한의, 따라서 온전한 권한을 갖는 것들이다. 이렇게 미술을 통해 주제를 다루고 이야기를 전함으로써 그는 “정보를 배타적으로 독점”하여 전문가들 사이에서만 향유될 뿐인 1970년대 한국의 형식주의적 모더니즘을 넘어서고자 했다. 이런 맥락에서 그의 미술은 의미, 서사, 소통이 복귀하는(혹은 비로소 시도되는) 1980년대 이후 한국미술의 ‘반형식주의적’ 경향과 함께했다고 말할 수 있다. 그러나 그는 ‘반형식주의적’이기 위해서 형식을 고려하는 일이 중요하다고 생각했다. 효과적으로 의미를 전하고 소통하기 위해서 다름 아닌 재료, 매체, 기법, 크기, 비유, 전시장 및 관객의 조건 등 작품이 경험되는 형식을 면밀히 따져보고 전략적으로 고안해야 한다고 말이다. 이런 점에서 그의 형식주의란 의미를 거부하기에 순정하다고 간주되는 시각적 구성과 형태를 실험하는 1970년대의 것도, 그렇다고 형식이란 내용의 전달체에 불과하니 관습적인 형식이라도 ‘진실’을 담으면 자동적으로 통할 것이라 믿는 1980년대의 것도 아니었다. 이와 같은 형태론적 형식주의나 물신주의적 형식주의를 거부한 그가 추구한 것은 수사학적 혹은 구조적이라 부를 수 있는 종류의 형식주의였다. 바로 이점이 1990년대 이후 한국미술의 전개에 있어서 윤동천의 기여였다.

의미를 전하고 나누는 데 있어서 핵심은 진실보다는 설득력일 것이다. 작가는 진실을 강변하는 일이 오히려 사람들에 다가가기보다 그들을 밀어낼 수 있다고 생각했다. 시대적 요구의 시급성 속에서 진실이면 족하던 시기가 지나가고 있음을 감지하고 있었다 말하는 것이 더 정확할지 모른다. 관객을 깨닫게 하는 일을 넘어 감동을 전하고 행동으로 이끄는 일이 그의 소망이라면, 관건은 진실을 말하는 일보다 그것을 얼마나 납득할 수 있게, 다른 말로 하면 얼마나 ‘매력적’으로 관객과 나눌 수 있을지 고민하는 일일 것이다. 따라서 그 고민은 이미 미학적인 문제이다. 어떤 의미에서 그는 자신의 미술이 무엇을 말하고자 하는지 스스로 한정한 바 있기에(“나”, “미술”, “우리”) 많은 작가들을 괴롭히는 그 본원적인 질문으로부터 해방되었고 그로 인해 온전히 ‘어떻게’, 즉 형식에 힘을 모을 수 있었다고 말할 수 있을지 모른다. 그런데 이는 달리 보면 매번 형식에 대한 고민을 감내하게 되었다는 말이기도 하다. 전하고자 하는 내용에 따라 회화, 판화, 오브제, 사진, 설치 등 모든 매체를 아우른다는 그의 언급은 모더니즘의 매체특정성으로부터 해방된 ‘포스트모던’ 혹은 ‘포스트매체’의 느긋한 유연함을 드러내는 것만은 아니다. 그만큼 자유를 대가로 매 전시와 작품마다 고통스러운(“머리에 쥐가 나는”) 선택을 해야함을 시사한다.

형식에 대한 면밀한 고려는 여러 수준에서 진행된다. 그러나 초점은 관객을 현상학적 풍부함으로 이끄는 조형 요소의 구성이라기보다, 의미작용으로 초대하기 위한 전시장 내 작품들 사이, 설치나 포토-텍스트 같은 한 작품 내 구성요소들 사이, 혹은 작품과 제목의 사이의 수사학적 관계에 놓인다. 그의 전시에 들어선 관객은 작가가 세심하게 짜놓은 의미망 속으로 진입하게 되는데, 일상에서 가져와 배열된 그리 대단치 않은 물건(혹은 이미지)과 말들은 모종의 상상적 연결 혹은 조합을 유도하여 그 즉물적 면모 밖에서 의미를 끌어오게 만든다. 이와 같은 의미의 그물을 엮어내는 작가의 가장 특징적인 구조 내지 형식은 환유이다. 그것은 개념적 유사성을 기반으로 하는 은유와 달리 물리적 인접성을 원리로 한다. 시공간적으로 붙어있는 관계라는 점에서 그 연관은 직접적이고 필연적인(혹은 “지표적”) 면이 있다. 예를 들면, 윤동천의 작품에서 권총은 권력층을, 스패너는 노동자를, 책은 지식인을, 목발은 불구의 몸, 개는 흔한 욕설로 이어지는 등이다. 이와 같은 연상은 깊이 있는 울림을 주지만 비의적일 수 있는 은유와 달리 상식적이고 객관적이다. 또한 은유의 경우에서처럼 기표가 기의로 대체되기보다 그 자체로 구체적이고 감각적으로 작동한다(예를 들어, 개의 이미지는 욕설을 떠올리게 하지만, 동시에 개는 또 무슨 죄인가라고 생각하게 만든다). 따라서 의미가 고정되지 않는다. 이처럼 의미화된 개별 유닛들을 여러 방식으로 결합시키며, 즉 ‘인접’시키며 나름의 구문을 짓게 만든다는 점에서 또한 환유적이다. 이렇게 윤동천의 작품은 고도로 응축된 깊이를 갖는 어휘로 구성된 시라기보다 비근한 낱말로 의미가 맺어지고 이어지는 산문에 가깝다. 그는 시의 지위로 고양되고 승화된 미술을 다시금 일상에서 이어지는 산문의 세계로 발 딛게 하려는 듯 보인다.

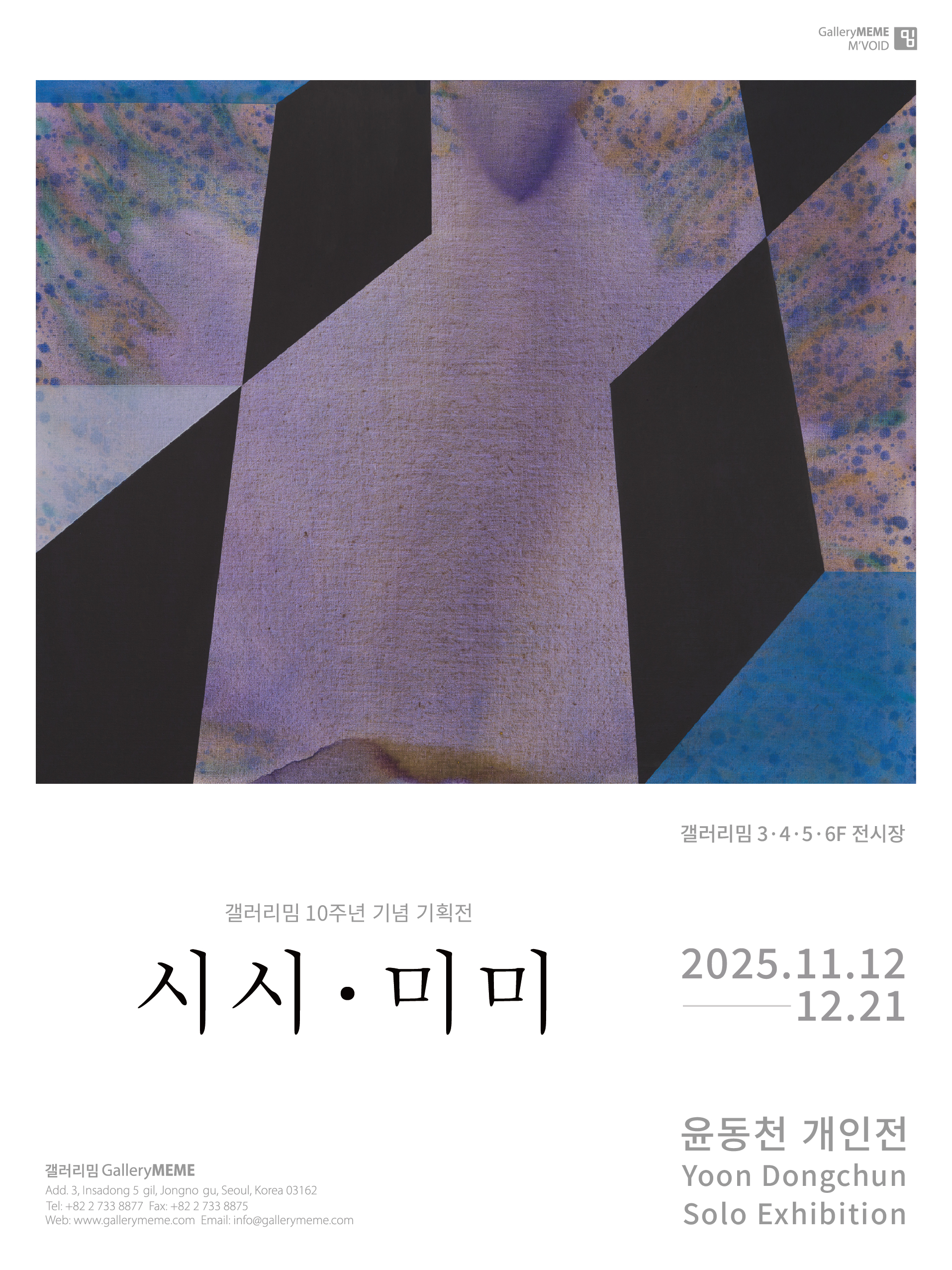

이번 전시에서 윤동천은 추상을 선보인다. 여기서 조형은 작가 내면의 ‘내적 필연성’에 따른 것도, 자연이나 사태의 본질을 추출해 낸 것도 아니다. 오히려 그의 삶에 놓인 단편적인 에피소드들에 등장하는 구체적인 물건이나 장소의 감각적 단면들이다. 설레면서 두려웠던 ‘빨간책’의 경험을 기술하면서 붉은색 사각형을 화면 안에 비스듬히 얹어놓고, 대입 낙방 후 자취를 하며 마신 소주를 떠올리며 연하늘색 원을 화면 가운데에 올려놓는다. 이들은 그의 삶의 본질 내지 요체를 담아낸 시각적 은유가 아니다. 추상적 명제로 환원될 수 없는 삶의 감각적이고 구체적인 환유들이다. 이와 같은 그의 산문적 추상, 혹은 환유적 추상은 번뜩이는 통찰이나 깊이 있는 함축으로 호소하지 않는다. 미술에 대한 그와 같은 흔한 기대에 부응하지 않는다. 대신 미술은 그렇게 어렵게, 간헐적으로 만날 수 있는 것이 아니라 일상에 편재해있음을 말한다. 감동이 저 먼 곳에 있는 소중한 것이 아니라 언제나 우리 주변에 놓여있듯이 말이다.

* 이 글이 참조한 문헌은 다음과 같다. 형식주의에 대해서, Yve Alain-bois, Painting as model (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990); 은유와 환유에 대해서, 서영채, 『인문학 개념정원』, 문학동네, 2013; 그리고 윤동천의 미술에 대해서,『윤동천 YOON DONGCHUN』, 소요서가, 2022.

Yoon Dongchun’s Formalism

Shin Chunghoon (Art Critic/professor of Seoul National University College)

“Formalism” is a misnomer, or even a vexatious term for Yoon Dongchun’s art. That is because he has never mentioned or proposed formalism in relation to his work, but on the contrary has always emphasized that his art is to convey and share meaning, not form. According to the artist, his themes concern issues of himself, issues of art, and issues of our society, which are the least he can express as a subject, artist and citizen, and therefore things over which he has full authority. Thus, by dealing with themes and conveying stories through art, Yoon sought to overcome the Korean formalist modernism of the 1970s, which “exclusively monopolized information” and was enjoyed only among specialists. In this context, we can say that his art has proceeded side by side with the “anti-formalist” trends of Korean art since the 1980s, during which significance, narratives and communication were restored (or finally attempted). Yoon, however, thought it was important to consider form in order to be “anti-formalist.” One must carefully consider and strategically invent forms through which artworks are experienced, such as materials, media, technique, size, analogies, exhibition space and conditions of the spectators, in order to effectively convey meaning and communicate with viewers. In this sense, his "formalism" is neither that of the 1970s, which experimented with visual compositions and shapes considered pure because they rejected meaning, nor that of the 1980s, which believed that even customary forms would automatically be understood since form is nothing more than a transporter of content. Rejecting such morphologic and fetishist formalism, what he pursued was the kind of formalism that could be called rhetorical or structural. This is Yoon’s contribution to the development of Korean art since the 1990s.

The core of communicating and sharing significance is persuasiveness, rather than truth. The artist thought that arguing the truth to people might push them away, instead of allowing him to approach them. Perhaps it would be more accurate to say he sensed that the era was passing in which the truth was enough for the urgent demands of the times. While his hope is to go beyond making the spectators aware, to emotionally move them and lead them to action, the key to achieving this hope is thinking how to “charm” spectators with the truth so that they fully understand. Therefore, this concern is already an aesthetic one. In a certain sense, he has set the boundaries for his own art, what it is trying to say (“me,” “art,” “us”), and is consequently liberated from the fundamental question that torments artists. Perhaps one can say this enabled him to focus his strength on the “how,” or the form. But from a different angle, it also means that he had to agonize over the form each time. His comment that his scope of media includes everything from painting to printmaking, objet, photography and installation, does not just reveal the relaxed flexibility of “postmodern” or “postmedia,” liberated from the medium-specificity of Modernism. It suggests that in exchange for freedom, he has had to make painful (“brain-cramping”) choices for every exhibition and every work.

The careful consideration of form takes place at many levels. The focus, however, is not on the composition of formal elements that lead spectators to phenomenological abundance, but rather the rhetorical relations between the works in the exhibition, between the composing elements of each work, such as an installation or photo-text piece, or between a work and its title. Going to his exhibition, one enters a semantic network elaborately woven by the artist. The not-so-impressive objects (or images) and words, which he brings from daily life and arranges, induce a certain imaginary connection or combination to bring in meaning from outside their literal appearances. The most characteristic structure or form used by the artist to weave such a network of meaning is metonymy. Unlike the metaphor, which is based on conceptual similarity, the principle of metonymy is physical proximity. In that it is a relationship attached in time and space, the connection has a direct and inevitable (or “indicative”) side to it. For example, in Yoon’s work, the pistol is the powerful class, the spanner is the working class, the book is the intellectual, the crutch is the disabled, and the dog is a common curse word. Such associations give deep resonance, but unlike metaphors, which can be esoteric, they are sensible and objective. Moreover, compared to the case of the metaphor, in which the signifier is replaced by the signified, they function concretely and sensuously in themselves. (For example, the image of the dog reminds you of a swear word, but at the same time makes you ask what the dog is to blame for). Therefore, the meaning is not fixed. Hence, the work is also metonymical in that it makes you create your own sentence structure, while combining—adjoining—individual signified units in various ways. In this way, Yoon’s work is closer to prose, in which meaning is linked and connected with common words, rather than poetry consisting of vocabulary of highly condensed depth. It seems if he is trying to make art, which has been sublimated to the status of poetry, once again tread the world of prose, being carried on in everyday life.

In his exhibition, Yoon presents abstraction. Here the forms are not according to the artist’s “inner inevitability,” nor are they extractions from the essence of nature or situations. Rather, they are sensuous cross-sections of specific objects or places that appear in the fragmentary episodes positioned in his life. He places a red rectangle obliquely in the picture-plane while writing about his experience of the “red book,” which was both anticipative and frightening; and puts a light sky blue circle in the center of another picture-plane, recalling the soju he drank while living on his own after his failure to enter college. These are not visual metaphors capturing the essence or key factors of his life. They are sensuous and concrete metonyms that cannot be reduced to abstract theses. Such prosaic abstractions, or metonymical abstractions, do not appeal to viewers with brilliant insight or profound implication. They do not meet such common expectations for art. Instead, they say that art is not something you must meet with difficulty, or only intermittently, but is something omnipresent in daily life. After all, the experience of being deeply moved is not a faraway precious thing, but something that is always around us.

* This text used the following references: on formalism, Yve Alain-bois, Painting as model (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990); on metaphor and metonymy, Seo Young Chae, Concept Garden of Humanities, Munhakdongne, 2013; and on Yoon Dongchun’s art, YOON DONGCHUN, Soyoseoga, 2022.

시시•미미(微微) 전시에 부쳐

이 전시는 대단하고 멋진 것이 아니라, 시시하고 미미한 것에 대한 관심으로 비롯되었습니다.

이는 주제, 소재, 작업 방식(형식) 모두를 아우릅니다.

현실에서는 다소 영향력을 갖지만 미술로 표현하기에 적합지 않거나,

미술사적으로는 중요하지만 일반에게는 큰 의미를 갖지 못하는 내용이거나,

전반적으로 시각적으로나 의미로나 크게 볼품없다고 여겨지는 것들에 대한 환기와 주목입니다.

하지만 의외로, 그리고 당연히, 소중합니다.

과장되게 표현하면 늘 변혁의 시발점이었습니다.

윤동천의 시시·미미

윤동천은 이번 전시에서 제목이 이야기하듯 ‘시시하고 미미한 것’들을 전시장으로 데려온다. 어떻게 시시하고 미미한 것들이 ‘미술’과 함께 있을 수 있을까. 그는 그만의 독자적인 어법을 이번 전시에서도 펼쳐놓는다. 이 펼쳐놓음의 기술(技術)은 미술하기의 원초적인 즐거움을 얼마만큼 현실 안팎에서 허용할 수 있는가의 문제를 데리고 논다. 미술이 다루기엔 너무 시시한 사물들을 대상으로 하는 하지만, 그가 촬영한 사진들의 구도와 형식, 표면의 질감을 보면 동서양 미술사의 오랜 작업들이 탐구해온 시각과 재현, 구상과 추상의 문제가 녹아있다는 생각이 든다.

‘시시 미미’를 발음할 때 느낄 수 있는 모국어의 리듬감은 신선하다. 이번 전시는 변주와 변형의 놀이에서 출발하는 듯보인다. 그 귀착점이 어디인지는 작가가 보여주는 색과 형태, 시각적이고 의미를 지닌 것들의 수집과 발견을 따라가보는 데서 각자 찾을 수 있을 것이다. 윤동천이 명명한 ‘시시한 것들’은 그가 목격한 것들이다. 또 이 ‘미미한 것들’은 그가 추상 회화 작업인 <단순연작>와 <덩이>들로 나아가게 하는 구체적 모티브가 된다. 어린아이의 놀이같기도 하고 철학적인 의제같기도 한 단어의 조합은 우리가 살아가는 현실의 다양한 측면과 유사하다. 그는 이렇게 서로 다른 것들의(미술=현실, 미술/현실) 조합을 통해 한국의 정신사적인 리얼리티를 눈앞에 마주하게 한다.

자, 전시장을 보자. 전시장의 각 층층은 윤동천의 미술관이며 동시에 한국의 현대사를 문맥화하는 시각적인 생활 박물관이다. 5층에 있는 ‘익숙한 문구들’ 연작을 보자. 합판에 레이저로 제시된 문구들에서 구체성과 보편성을 띠는 언어들의 합주를 볼 수 있다. 인생에 대한 처절한 경험 없이는 도달할 수 없는 구체성을 띠는 ‘생활’ 언어들이 인생의 쓴맛 단맛 짙은 맛을 알려준다. 전시장 통로의 벽면에 위치한 <기념일>(2005)은 어떤가. 종이 위에 잉크로 새겨진 이 작은 날짜들은 윤동천이 기억하는 한국 현대사의 ‘기념일’이다. 어린시절부터 성인이 될 때까지 그에게 파노라마처럼 펼쳐졌을 사건들이 작은 글자들로 낱장의 얇은 종이 위에 남겨져 있다. 이것은 일종의 ‘카운터 모뉴먼트(counter monument : 반기념비)’로서, 기념비의 육중함에 반대하는 또 다른 형식의 ‘기억 작업’이다. 작가는 이렇게 한국 현대사가 거대하게 기억해온 시간성을 윤동천 개인의 감각으로 뒤집는다. 이때 개인은, 작가가 오랜 시간 이야기해왔듯 공공적 실천과 집단의 무의식을 외면하지 않는 개인이다.

윤동천의 미술은 그러므로 풍자가 아니라 다른 방식의 기억이다. 또 이것은 미술과 현실의 질긴 관계를 그의 식으로 말하는 행위다. 6층에 자리한 <시시한 오브제> 연작에서 작가는 현실의 사물에 깃든 관습을 현실의 지리멸렬한 통념들과 맞부딪히게 한다. 빗자루, 펜, 요강, 톱에 이르기까지, 작가는 일상에서 언제나 주변부의 자리를 차지하거나 ‘이것이 거기 있다’는 식의 존재하는 것조차 알아차리기 힘든 미약한 사물들을 예의 주시하게 만든다. 윤동천이 붙인 작업의 제목은 작업의 일부가 되어, 관객과 작업이 만나는 시간과 공간을 확장시킨다. 그래서 우리 관객들은 이 작업들의 말걸기를 외면할 수 없다.

그것은 작가의 내면 세계나 미술 내부의 암묵적 합의가 붙인 제목과 달리, 누구나 사용할 수 있고 누구나 만질 수 있는 것들(껌, 물병, 달걀)의 ‘다른 차원’을 열어두는 제목들이다. 예로 플라스틱 물병이 종이처럼 구겨져 있는 <100도씨의 힘>, 접시위에 씹던 껌을 만든 <스트레스를_씹다>를 보라. <입사지원서를 쓸 때마다 새 펜으로 서명하기로 마음먹었다>(2025) 앞에서 펜 100자루를 세어보며 하나씩 펜이 사라지는 장면을 상상하게 된다. <포획 포식 피식>(2025)이라는 제목을 지닌 쇠봉과 거미줄을 재료로 하는 작업 앞에서 미술사에 길이 남을 마르셀 뒤샹의 ‘큰 유리’가 떠올랐고 이와 동시에 어쩌면 거미가 여기 어딘가 실재할지도 모른다는 생각이 들었다. 공존하기 어려운 전시장 안의 ‘현실’이었다.

실로 전시장에는 작가가 아세테이프위에 아클릴릭으로 만든 거미 한 마리가 있다. 흰 벽에 붙어있지 않고 수직으로 서 있는 이 <거미>(2025)는 전시장에 있는 작업들의 ‘현재 위치’를 다시 한 번 쭉 살펴보게 했다. <뭉크 ‘절규’의 새 버전>으로 이름 붙은 작업에서 소리 내는 닭 인형이 살짝 천정을 보고 세워져 있는 것을 보았는지? 작가 윤동천이 세밀하게 관찰하고 시각적 리듬과 모양에 주목하여 대상의 시선을 배치하고 있다는 것을 알 수 있다.

작가는 언제나 현실을 주도면밀하게 ‘보는 사람’으로서, 풍경들을 관찰한다. 두 개의 사진을 배치하는 <시시한 풍경> 연작과 캔버스에 아크릴릭으로 그린 <시시한 대상으로부터> 회화 연작은 모두, 그가 이 현실에서 얼마나 철저하게 ‘보는 사람’으로 복무하는지 보여준다. 그런 점에서 내가 생각하는 그의 독자성은 ‘예술의 일상성’과 비판성이 한 자리에 공존할 수 있도록 하는 것이다. 그의 미술은 쉬운데 어렵고, 어려운데 쉽다. 이 무슨 형용 모순인가? 그러나 그래서 그의 미술하기는 작가가 세운 질서와 외부의 현실 세계가 함께 있다(공존한다). 현실에서 발견한 사물과 풍경의 일부는, 그가 그린 <잔설>과 <큰 주걱>처럼, 온전하지는 않지만 부분으로서 우리 곁에 있고 그래서, 예측불가능하게 아름답다.

현시원 (미술비평·연세대학교 커뮤니케이션대학원 교수)

Yoon Dongchun : Trivial·Subtle

In this exhibition, Yoon Dongchun brings into the gallery what the title itself suggests—“trivial and subtle things.” But how can such small, seemingly insignificant things coexist with “art”? Once again, Yoon unfolds his own distinctive artistic idiom. His art of “laying things out” poses a question: to what extent can the primal joy of making art be permitted—both within and beyond reality? Although his chosen subjects may seem too mundane for art to handle, the compositions, forms, and surface textures of his photographs evoke a lineage of artistic inquiries from both East and West—about vision and representation, figuration and abstraction.

The Korean title “Sisi Mimi” (meaning “Trivial·Subtle”) carries a fresh, rhythmic resonance. The exhibition seems to begin as a play of variation and transformation. Where it ultimately leads will be discovered individually by each viewer, as one follows the presentation of colors and forms, and the acts of collecting and recontextualizing objects charged with visual and semantic meaning. The “trivial things” he names are those he has witnessed. The “subtle things” serve as concrete motifs that lead him toward his abstract painting series, <Simple Shape> and <Lump>. The interplay of words, oscillating between the innocence of a child’s play and the depth of a philosophical discourse, mirrors the diverse aspects of the reality we live in. Through this combination of seemingly disparate realms (art = reality, art / reality), Yoon confronts us with a form of Korean spiritual-historical reality.

Now, let’s step into the exhibition space. Each floor serves as both Yoon Dongchun’s personal museum and a visual ethnography of contemporary Korean history. On the fifth floor, the series <Familiar Phrases> presents laser-engraved text on plywood, forming a polyphony of language that is at once concrete and universal. These “everyday” expressions, infused with the raw texture of lived experience, reveal life’s bitter, sweet, and complex flavors. On a corridor wall hangs <Anniversary> (2025)—a work in which dates printed in ink on paper record moments from Korea’s modern history as Yoon remembers them. The thin sheet of paper, inscribed with small letters, unfolds like a personal panorama of events from his childhood to adulthood. The work functions as a “counter-monument”: a mode of remembrance that resists the heavy permanence of a monument. By reframing historical time through his individual sensibility, Yoon inverts the grand temporality of Korean modern history. The “individual” here—consistent with his long-held stance—never turns away from collective consciousness or public engagement.

Yoon’s art, therefore, is not satire but an alternative form of remembrance. It is his way of articulating the tenacious relationship between art and reality. In the <Trivial Objects> series on the sixth floor, he confronts the conventions embedded in everyday things with the fragmented common sense of our reality. Brooms, pens, chamber pots, saws—these humble objects, often relegated to the periphery of daily life, become subjects of attentive observation. Their very titles, integral to each work, extend the temporal and spatial encounter between artwork and viewer. We, the viewers, cannot easily turn away from their subtle address.

Unlike titles derived from private symbolism or art’s implicit conventions, Yoon’s titles open up another dimension of the things anyone might touch or use: gum, a plastic bottle, an egg. <The Power of 100°C > (2025) presents a crumpled plastic bottle as if it were paper; in <Chewing_Stress> (2025), a wad of gum rests neatly on a dish. Standing before <I Decided to Sign Every Job Application with a New Pen> (2025), we find ourselves counting the hundred pens lined up, imagining them slowly disappearing one by one. Before <Capture·Consume·Chuckle> (2025), made with an iron rod and spiderwebs, we recall Marcel Duchamp’s “The Large Glass”—and at the same time, wonder whether a real spider might be lurking somewhere in the gallery. It is a “reality” that can hardly coexist with the exhibition space.

Indeed, there is a spider in the exhibition—an acrylic one painted on acetate tape. Standing upright rather than clinging to the wall, <Spider> (2025) invites us to reexamine the “current positions” of all surrounding works. Did you notice that the squeaky rubber chicken, titled <A New Version of Munch’s “The Scream”>, stands slightly tilted toward the ceiling? It is a small but eloquent sign of Yoon’s meticulous attention to visual rhythm, form, and the direction of gaze.

Yoon Dongchun is, above all, a precise observer of reality. His series of paired photographs, <Trivial Landscapes>, and acrylic paintings, <From Trivial Subjects>, both reveal how thoroughly he serves as a “viewer” within this world. The artist’s originality, I believe, lies in how he allows the everydayness of art and its critical dimension to coexist. Yoon’s art is easy yet difficult, difficult yet easy—a paradox, perhaps, but one that perfectly captures how his practice maintains a fragile balance between the order he constructs and the external reality it encounters. Like those in <Remaining Snow> (2025) and <Large Ladle> (2025), fragments of objects and scenery drawn from the real world may not appear whole, but still remain beside us as partial presences. In that incompleteness lies a beauty that is, quietly and unexpectedly, profound.

Hyun Seewon

(Professor, Graduate School of Communication, Yonsei University / Art Critic)

윤동천 Yoon Dongchun

b. 1957

서울대학교 미술대학 서양화과 명예교수

1987 크랜브룩 아카데미 오브 아트 졸업

1985 서울대학교 미술대학 회화과 졸업

SOLO Exhibition (selected)

2025 시시·미미, 갤러리밈, 서울

지금 우리에게 필요한 것들 _ 진부한 제안, WWNN, 서울

2024 위대한 퍼포먼스, 공간형, 서울

2023 이면, 아트조선스페이스, 서울 (회화, 판화, 드로잉, 설치)

추상에 관하여, 갤러리밈, 서울

2022 쌍-댓구, 갤러리 시몬, 서울 (회화, 설치, 영상)

산만의 궤적, 서울대학교미술관, 서울

2017 일상_의, 금호미술관, 서울 (회화, 설치, 영상)

2014 병치-그늘, 신세계갤러리, 서울 (드로잉, 판화, 설치)

2013 Simple Edge, EN갤러리, 나가노, 일본 (회화, 판화, 드로잉)

2012 도구들, 갤러리호무라, 삿포로, 일본 (설치, 판화)

2011 탁류, OCI미술관, 서울 (회화, 설치, 판화)

2007 망루, 금호미술관, 서울 (회화, 드로잉, 사진, 설치)

2005 조건부 무작위, 와이트월갤러리, 서울 (회화, 설치, 드로잉)

2003 오랫동안 메마른 강바닥, Temporary Space, 삿포로, 일본 (설치, 드로잉)

2001 뻔한, Allcott 갤러리, 채플힐, 미국 (사진, 설치)

1999 차이, 성곡미술관, 서울 (회화, 설치, 영상)

1998 그림-문자-공공, 일민미술관, 서울 (설치)

1995 만화경: 의미 있는 사물들, 국제갤러리, 서울 (설치)

1992 다른 양식들, 샘화랑, 서울 (회화)

생각하는 그림, 갤러리인데코, 서울 (설치)

제 11회 석남미술상 수상 기념전, 박여숙화랑, 서울 (회화, 사진)

1991 평론가가 선정한 ‘90년대 전망전, 가나화랑, 서울 (회화)

윤동천, 판화, 최갤러리, 서울 (판화)

1989 희망의 나라로, 나우갤러리, 서울 (설치)

1988 윤동천, 갤러리현대, 서울 (회화, 설치, 판화)

GROUP Exhibition (selected)

2025 Plate On/Off, 답십리 아트랩, 서울

선농미술전, 갤러리라메르, 서울

도시의 몽상, Soluna Fine Art, 홍콩

우리들의 낙원, 문화역서울284, 서울

묵운동휘(墨韵同辉), 허베이 미술대학, 중국

검은 악몽의 집단치료, 플레이스막3, 서울

한국현대미술 하이라이트, 국립현대미술관, 서울

2024 this is today, 공간형, 서울

우리가, 바다, 경기도미술관, 안산

모호한 경계, 필갤러리, 서울

소장품전, 서울대학교미술관, 서울

2023 선농미술전, 갤러리라메르, 서울

No Frame, 성신여자대학교 수정관 가온 전시실, 서울

2022 백남준 효과, 국립현대미술관, 과천

긴 호흡, 토포하우스, 서울

선농미술전, 갤러리라메르, 서울

오후 6시는 무슨 색일까?, 베카갤러리, 서울

2021 공(空), 서소문성지 역사박물관, 서울

NFT BEGINS, 사이아트센터, 서울

선농미술전, 갤러리라메르, 서울

포스트프린트 2021, 김희수아트센터, 서울

2020 1+1=0, 갤러리 로직, 서울

한국의 현대판화, 오리엔탈미술관, 모스크바 / 사마라주미술관, 사마라 / 러시아

금호미술관 소장품전, 금호미술관, 서울

판화, 판화, 판화, 국립현대미술관, 과천

Collections

뉴욕 공공 도서관 (뉴욕, 뉴욕주, 미국), 프레스노 예술센터 및 박물관 (프레스노, 캘리포니아주, 미국), 곤자가대학교 (스포케인, 워싱톤주, 미국),

미시간 아트레인 (앤 아버, 미시건주, 미국), 팔로 알토 시회 (팔로 알토, 캘리포니아주, 미국), 캘리포니아주립대학교 (롱비치, 캘리포니아주, 미국),

그린넬대학교 (그린넬, 아이오아주, 미국), 대영박물관 (런던, 영국), 뉴올리언스박물관 (뉴올리언스, 루이지아나주, 미국),

서울시립미술관 (서울), 토탈미술관 (서울), 일민미술관 (서울), 성곡미술관 (서울), 신세계미술관 (서울), 국립현대미술관 (서울),

금호미술관 (서울), 진천군립생거판화미술관 (진천), OCI미술관 (서울), 양구군립박수근미술관 (양구), 서울대학교미술관 (서울), 제주도립미술관(제주)

Awards

2023 제35회 이중섭 미술상 수상

1992 제 4회 국제 아시아 유럽 비엔날레 금상

1992 제 11회 석남미술상

1991 제 1회 토탈미술상 관장상

Yoon Dongchun

b.1957

Professor Emeriti, Department of Painting, College of Fine Arts, Seoul National University

1987 Cranbrook Academy of Art (MFA)

1985 Seoul National University (BFA)

SOLO Exhibitions

2025 Trivial·Subtle, GalleryMEME, Seoul

What We Need Now, WWNN, Seoul

2024 Great Performance, Artspace Hyeong, Seoul

2023 The Other Side, Art Chosun Space, Seoul

about ABSTRACTION, GalleryMEME, Seoul

2022 Pairs, Gallery Simon, Seoul

Trail of Divergence, Seoul National University Museum of Art

2017 Ordinary, Kumho Museum of Art, Seoul

2014 Juxtaposition-Shade, Shinsegae Gallery, Seoul

2013 Simple Edge, EN Gallery, Nagano, Japan

2012 Tools, Gallery Homura, Sapporo, Japan

2011 Muddy Stream, OCI Museum of Art, Seoul

2007 Watchtower, Kumho Museum of Art, Seoul

2005 Conditional Randomness, White Wall Gallery, Seoul

2003 For a Longtime Arid Riverbed, Temporary Space, Sapporo, Japan

2001 Too Obvious, Allcott Gallery, Chapel Hill, USA

1999 Difference, Sungkok Art Museum, Seoul

1998 Power, Ilmin Museum of Art, Seoul

1995 Kaleidoscope: Meaningful Objects, Kukje Gallery, Seoul

1992 Different Styles, Gallery Sam, Seoul

Art for Thinking, Gallery Indeco, Seoul

The 11th Seoknam Art Prize, Park Ryu Sook Art Gallery, Seoul

1991 Critics' Choice of '90s Perspective, Gana Art Gallery, Seoul

Yoon Dongchun, Printmaking, Choi Gallery, Seoul

1989 Toward Land of Hope , Gallery Now, Seoul

1988 Yoon Dongchun, Gallery Hyundai, Seoul

GROUP Exhibitions (selected)

2025 Plate On/Off, Dapsimni Art Lab, Seoul

The Sunnong Artists Circle 2025, Gallery La Mer, Seoul

Urban Reveries, Soluna Fine Art, Hong Kong

Our Enchanting Paradise, Culture Station Seoul 284, Seoul

Ink Resonance, Shining Together, Hebei Academy of Fine Arts, China

Attitudes towards Contemporary Printmedia, Placemak 3, Seoul

Highlights of Korean Contemporary Art, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul

2024 this is today, Artspace Hyeong

Memory, Stare, Wish, Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art, Ansan

Ambiguous Boundary, Fill Gallery, Seoul

Collection, Seoul National University Museum of Art, Seoul

2023 The Sunnong Artists Circle 2023, Gallery La Mer, Seoul

No Frame, Sungshin Women’s University, Seoul

2022 Paik Nam June Effect, MMCA, Gwacheon

Long Breathing, Topohaus, Seoul

The Sunnong Artists Circle 2022, Gallery La Mer, Seoul

What Color Is 6 PM ?, Beka Gallery, Seoul

2021 Emptiness, Seosomun Shrine History Museum, Seoul

NFT BEGINS, Cyart Center, Seoul

The Sunnong Artists Circle 2021, Gallery La Mer, Seoul

Post-Prints 2021, Soorim Art Center, Seoul

2020 1+1=0, Gallery Logic, Seoul

The Sunnong Artists Circle 2020, Gallery La Mer, Seoul

Modern Graphics of South Korea, State Museum of Oriental Art, Moscow / State Art Museum in Samara, samara / Russia

Kumho Collections, Kumho Museum of Art, Seoul

Prints, Printmaking, Graphic Art, MMCA, Gwacheon

Collections

The New York Public Library (New York, NY, USA), Fresno Art Center And Museum (Fresno, CA, USA), Gonzaga University (Spokane, WA, USA),

Michigan Artrain (Ann Arbor, MI, USA), City of Palo Alto (Palo Alto, CA, USA), State University of California (Long Beach, CA, USA),

Grinnell College (Grinnell, IA, USA), British Museum (London, England), The New Orleans Museum of Art (New Orleans, LA, USA),

Total Museum of Contemporary Art (Seoul), Seoul Museum of Art (Seoul), Ilmin Museum of Art (Seoul),

Sungkok Art Museum (Seoul), Shinsegae Museum (Seoul), National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art_Korea (Seoul),

Kumho Museum of Art (Seoul), Jincheon Printmaking Museum (Jincheon), OCI Museum of Art (Seoul),

Park Soo Keun Museum (Yanggu), Seoul National University Museum of Art (Seoul), Jeju museum of art(Jeju)

Awards

2023 35th Lee Joong Seop Art Awards (Seoul)

1992 International Asia-Europe Biennale (Gold Prize) (Ankara, Turkey)

The 11th Seoknam Art and Cultural Foundation Award (Seoul)

1991 Total Grand Prix (President Award) (Seoul)