정직성

M’cube is a program to discover and support young artists who explore experimental territories with a passion for novelty and challenge their limits.

ABOUT

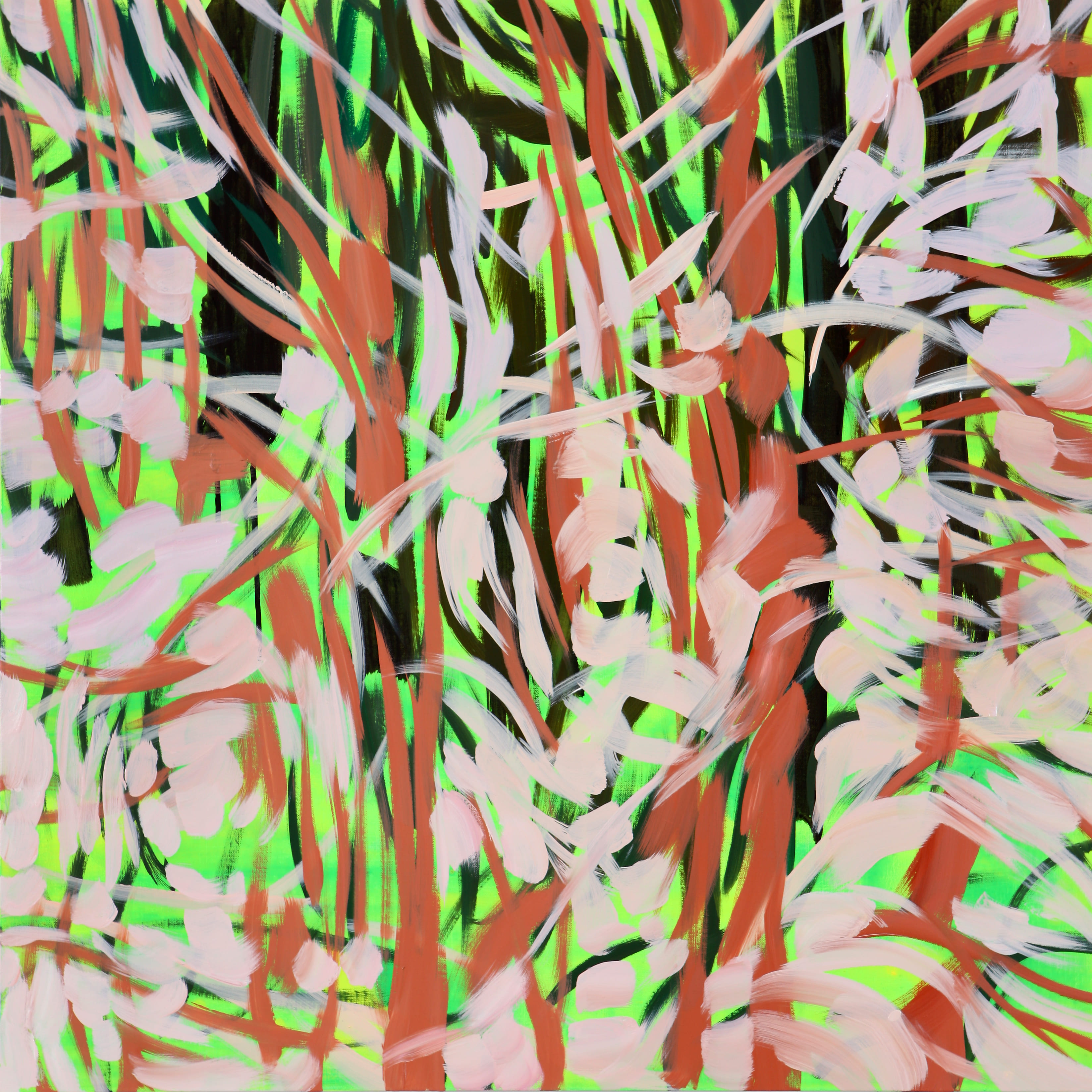

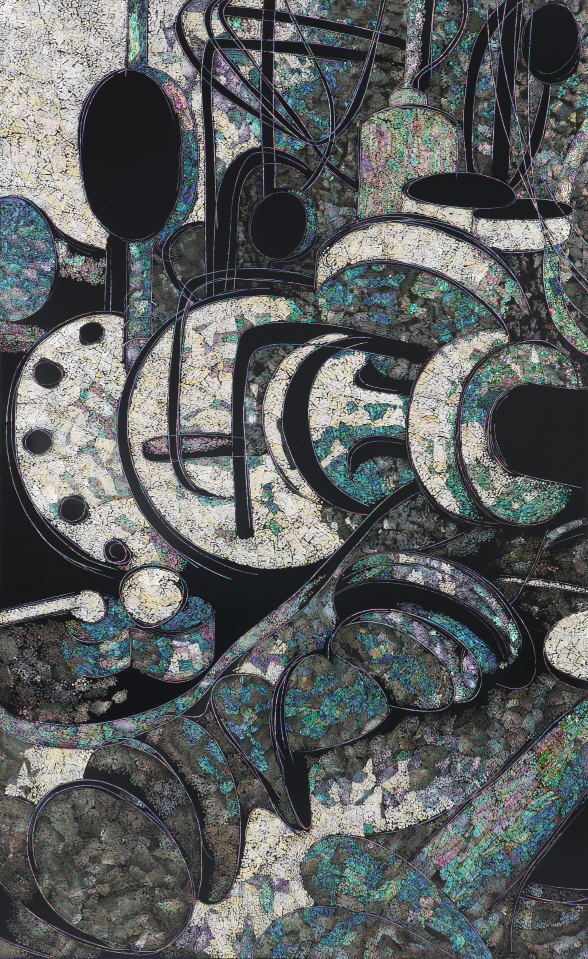

정직성(1976년 서울생)은 회화의 윤리적, 영적 역할과 역량을 고찰하고 실험하는 화가이다. 서울‧경기 지역을 중심으로 제주를 오가며 활동하고 있다. 2001년부터 <연립 주택>, <공사장 추상>, <푸른 기계>, <기계>, <밤 매화>, <겨울 꽃>, <녹색 풀>, <현대 자개 회화>, <표현하는 자연> 등 다양한 연작들을 발표했다. 2006년 첫 개인전 《무정형 구축》을 열면서 화단의 주목을 받기 시작했다. 서민 주거지역이나 노동자의 일터 등을 소재로 현실의 장소 특정적 감각을 추상표현주의적 필법이나 기하학적 추상, 모노크롬 형식 등을 차용하여 표현하는 알레고리적 메타회화 작업을 진행하였다. 최근에는 나전칠기 기법이나 사군자 등 한국적 상징성을 띠는 형식을 한국의 자연생태적 장소성을 기반으로 재해석하여 회화의 외연을 넓히는 시도를 하고 있다.

Jeong Zik Seong

Jeong Zik Seong (born in Seoul, 1976) is an artist who examines and experiments the ethical and spiritual roles and capabilities of painting. It is active in and out of Jeju, mainly in Seoul and Gyeonggi, South Korea. Since 2001, she has released various series of works such as

전시 서문

환기喚起에서 상기想起로

정직성의 삶이 우리에게 환유하는 것

영단어 ‘honesty’를 우리말로 하면 무언지 생각해 보자. 빌리 조엘의

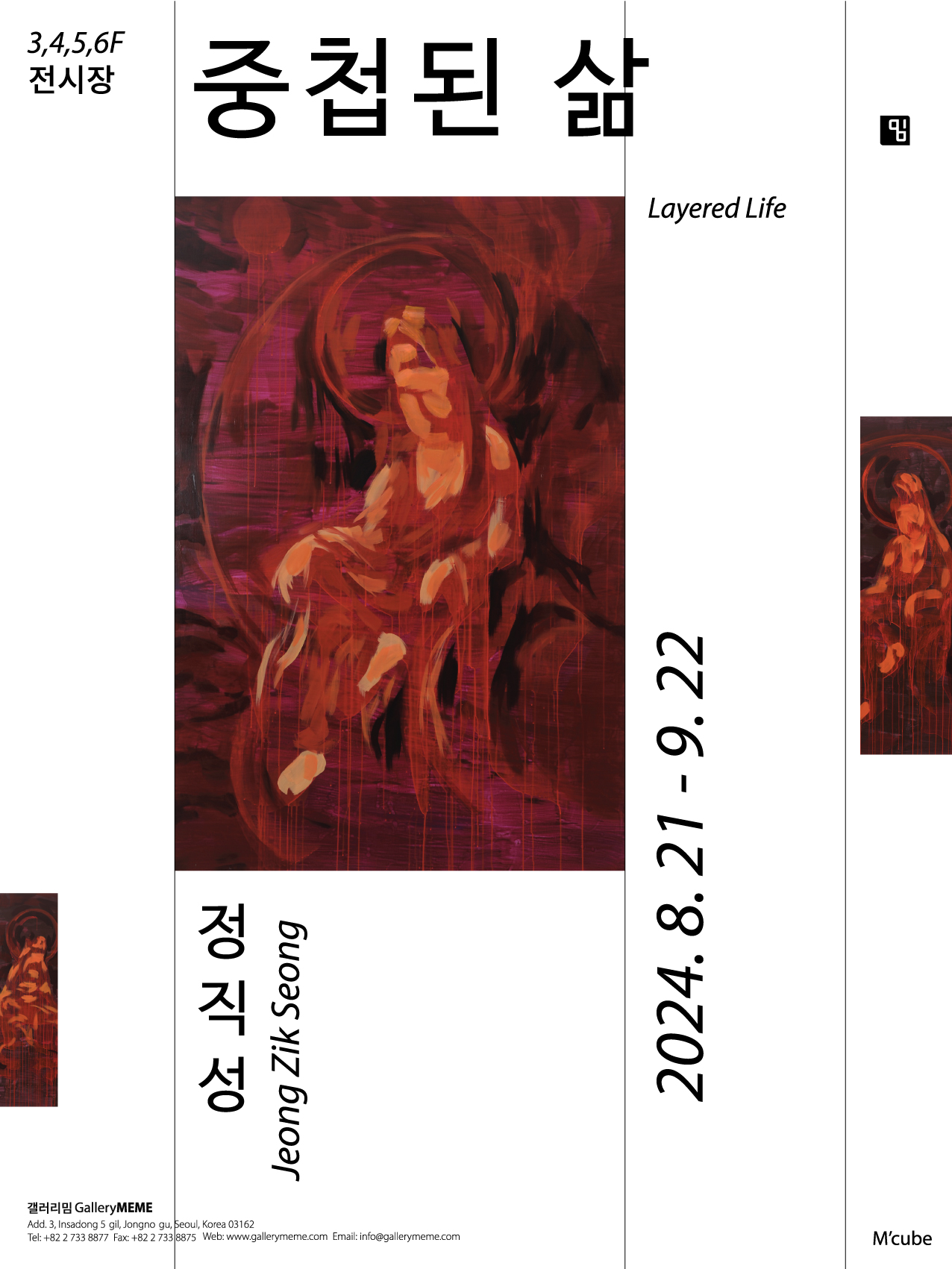

그러면서 정직성이라는 이름이 가진 일종의 언어적 속성을 넘어, 작업을 통해 나오는 그만의 정체성이 가히 ‘초월적인’ 영역을 넘나드는 무엇이 있지 않을까 하는 환상성을 갖게 하는 것은 작가로서도 유리한 지점일 것이다. 또한 그런 호기심과 지속적인 관심을 형성하게 하는 대중적이면서도 학술적인 아우라를 작가도 모를 리 없기에 부담도 되겠지만, 언제나 그렇듯 자신의 삶에 충실하고 치열하기에 이번 전시에서도 매력적인 제목 <중첩된 삶>은 그 자체로의 호소력은 물론 이곳 갤러리밈의 3층에서 6층까지의 네 층을 모두 활용함으로써 얻게 되는 구조적인 설득력을 갖추게 되었다.

“미술사에서 의미 있는 형식들을 가져와서 현재적인 의미를 띠도록 하는 작업들을 한다”고 종종 밝혀온 작가를 수식할 수 있는 말들 역시 다양한 형식으로 가능하다. 그리고 그것은 이러한 글에 의지하지 않고 감상자가 직관적으로 부여해도 된다. 다만 안내할 수 있는 재밌는 사실은 우리가 보통 회고전이 아니면 이러한 스펙트럼의 개인전을 보기 어렵고, 작가 역시 그만큼 준비된 상황이거나 이러한 컨셉을 수락하기 힘든 경우가 많지만, 정직성으로서는 벌써 세 번째 이와 같이 대규모적인 개인전을 치르는 점이라는 것이다. 그렇다면 여기서 한국의 감상자들이 느끼는 갈증, 혹은 자신도 모르게 허락하지 않고 있어 이중적이라 할 수 있는 부분을 짚고 넘어가고 싶다. 가령 고흐의 인생이 그의 그림과 어떤 연관이 있는지에 대해 거의 주입식으로 학습을 받고, 또 여러 매체를 통해 관심을 가지면서 ‘지금 우리 시대를 살아가는 현역 한국 작가 중엔 누가 있을까?’ 생각해 보면 별로 없다는 그 지점이다. 이에 대해 우리의 미술계가 그만큼 작품들이 매력적이지 않고 정보가 척박해서라고 단언할 수는 없다. 다만 그러한 형식의 전시가 별로 없다는 것은 분명하다. 그러한 점에서 이 전시는 정직성이라는 작가에 대해 더 잘 알 수 있는 소중한 기회일 것이다.

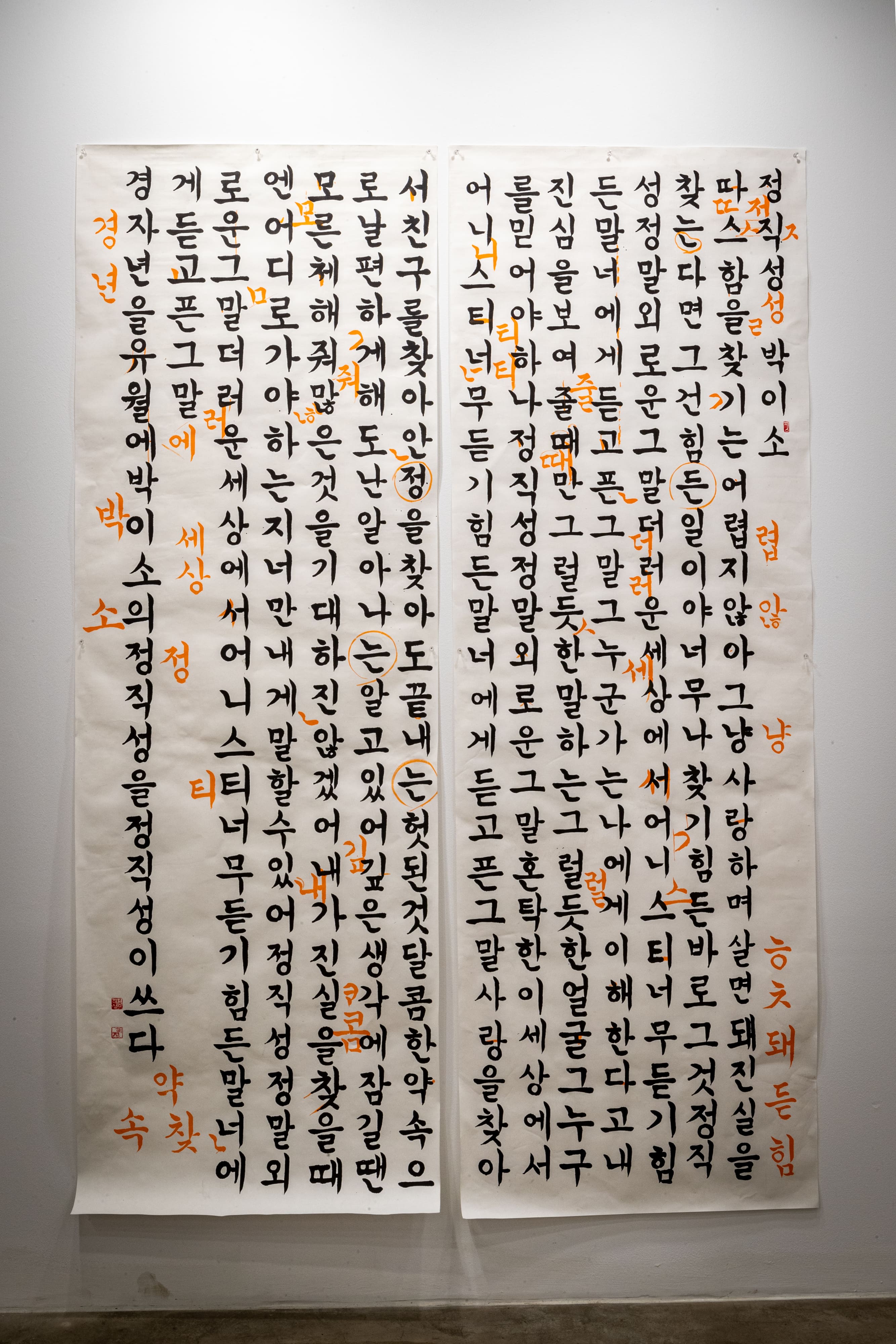

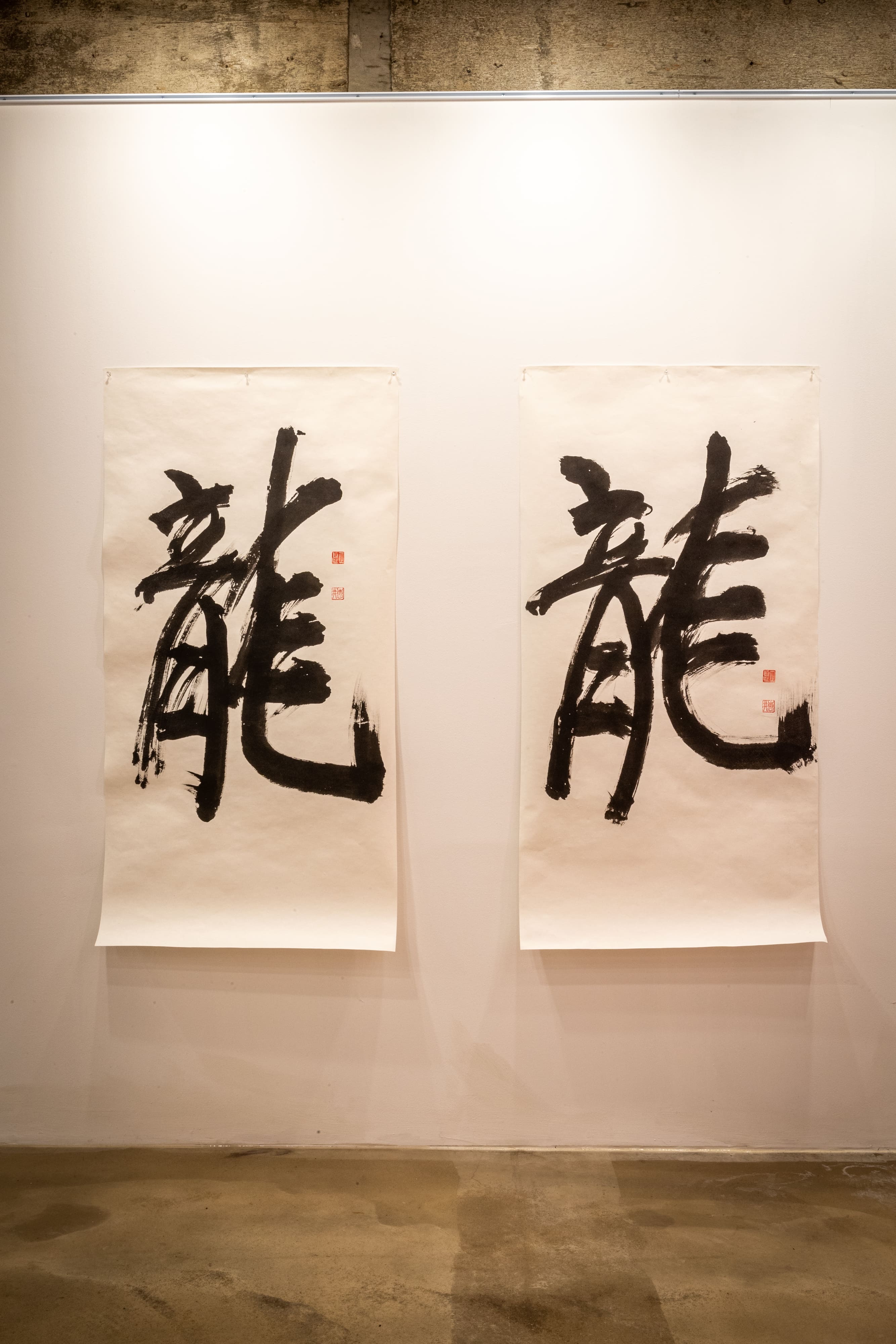

정직성의 세계는 무척 다양하다. 바라보는 상황부터 장르, 그리고 전시를 주도해 나가는 기획력까지 한 사람이 해내기 어려울 정도로 보이는 시간 속에 살고 있는 사람이다. 다행히 말과 글에 있어서도 자신에 대한 설명을 조리 있게 하고 수줍어하는 듯하면서도 굉장히 적극적이고 충실하게 임해 그러한 인터뷰 영상이 유튜브에도 여러 시기, 여러 채널에 걸쳐 올라와 있고 스스로 쓴 기획의 글이나 서문도 다수 존재한다. 가령 2020년 11월에 홍성에서 있었던 전시 <나 자신의 말My Own Words>에서 정직성은 전시 서문을 통해 “오랫동안 나 자신의 말을 하지 못했다. 무의식조차 언어로 구조화되어 있다는 자끄 라깡의 말처럼 표현하지 못한 나의 고통과 슬픔조차 이미 구조화되어 있기 때문일까, 그림과 말로 끄집어내려고 할 때 항상 그것과 너무 동떨어진 신파로 드러나 다시 보는 것이 더 괴로웠기 때문이었다. 하지만 이응노의 집에서 지내면서 가까이에서 접한 이응노 선생님의 생명력 넘치는 문자추상은, 문자는 그저 마음을 담는 그릇이라는 사실을 명백히 보여주는 듯했다. 그릇은 그저 마음을 담기 위해 빚어 구워내면 된다는 듯 여유롭고 자유로운 문자가 마음을 당당히 드러내고 있었다.”고 고백한 바 있다. 이러한 글은 그 당시의 전시에 대한 이해를 돕고 레지던시 생활 등이 작가에게 미치는 행복한 영향에 대해 대리만족감처럼 다가오는 예술가적, 정서적 측면을 제공할 뿐만 아니라, 어쩌면 전체 활동 중에서는 매우 일부라 할 수 있는 활동에서도 이러한 고민과 공간적, 시간적 맥락을 보여줌으로써 작가의 전체적 맥락을 파악하는 데 있어 큰 도움이 되는 효율적 측면마저 있다. 따라서 이 전시가 연대기적 나열은 아니므로 동선 편의상 6층부터 내려가며 감상하는 순서가 일반적이라고 할 때 처음 만나게 될 그 작업을 통해 관람자들은 정직성이 추구하는 다양함 가운데 흔들리지 않고 드러나는, 그러니까 애매하지 않은 자기표현의 수위와 맥락을 느낄 수 있을 것이다. 그것은 너무 전위적이려고 하다가 중심을 잃어 자기 자신은 별로 보이지 않는 역설적인 주체성 실종으로 가거나, 너무 하나의 색깔만 보여주려고 해서 작업이 아무리 좋더라도 지루해지는 쪽이 아니라 은연중에 한국인으로서의 정체성을 공유하면서도 민족주의적이지 않고, 여러 장르에 걸쳐 있으면서도 그 완성도가 다 높다는 점에서 소위 ‘팬심’을 갖게 하는 요소들의 힘이다. 그리고 여기서 가장 중요한 것은 추상과 구상의 이분법에서 벗어나 작가의 표현으로는 “냄새, 기억들이 함축되어 있는 상징들”까지도 드러낼 수 있는 ‘현장성’이 있다는 것이고, 그로 인해 역시 작가가 말하는 “보편성을 띠면서 다른 사람들과 공명할 수 있다는 것에 관한 확신”이 실제로 화폭과 여러 조형에 재현되고 있다는 점이다. 이는 이른바 ‘전형성’에 대한 새로운 가능성을 선사하며 일반적으로 어떤 예술의 덕목으로 통하던 ‘환기’의 기능을 좀 더 ‘상기’의 영역으로 예리하게 가져갈 수 있도록 하는 역할을 한다.

특정 평론가의 글을 끌어오는 것보다 지금 살아 있는 일반인이면서도 예술 향유자가 쓴 서술이 있어 활용하고자 하는 화제의 책을 잠시 빌리고자 한다. 10년 간의 실제 경험담을 일목요연하고도 현장성과 깊이 있는 서술로 담아낸 <나는 메트로폴리탄 미술관의 경비원입니다All the Beauty in the World>에서 저자 패트릭 브링리Patrick Bringley는, 베르나르도 다디Bernardo Daddi의 <십자가에 못 박힌 예수The Crucifixion>를 “메트에 소장된 작품들 중 가장 슬픈 그림”으로 지목하면서, “다디에게 그림은 고통스럽지만 꼭 해야 할 필요가 있는 생각을 돕는 도구였을 것”이라고 써 내려갔다. 그리고 “다디는 고통 그 자체를 그렸다. 위대한 예술품은 뻔한 사실을 우리에게 되새기게 하려는 듯하다. ‘이것이 현실이다’라고 말하는 게 전부다. 나도 지금 이 순간에는 고통이 주는 실제적 두려움을 다디의 위대한 작품만큼이나 뚜렷하게 이해하고 있을지 모르지만, 우리는 이내 그 사실을 잊고 만다. 점점 그 명확함을 잃어가는 것이다. 같은 그림을 반복해서 보듯 우리는 그 현실을 다시 직면해야 한다.”며 글쓴이로서의 가치관을 드러냈다. 통찰력이 있는 멋진 구간이다. 그런데 우리가 이러한 글을 읽으며 또한 드는 생각은, 그럼에도 불구하고 어떤 거리감 혹은 피상성을 느낀다는 것이다. 이것은 신앙심 유무에 대한 이야기도 아니고 동양인으로서 느끼는 서양 작품에 대한 괴리감도 아니다. 이는 그 작업이 개인의 심리에 미치는 영향의 거리 자체에 관한 이야기다. 그럴 때, 보통 글을 쓰는 입장에서도 거의 구분 없이 섞어 쓰고 있지만 사실은 본질적 차이가 있는 두 단어, ‘환기喚起’와 ‘상기想起’에 대해 말해볼 필요가 있다. 사전적으로, ‘환기’는 “주의나 여론, 생각 따위를 불러일으킴”으로 짧게 정의되어 있다. 반면 ‘상기’는 “한 번 경험하고 난 사물을 나중에 다시 재생하는 일. 플라톤의 용어로, 인간의 혼이 참된 지식인 이데아를 얻는 과정. 인간의 혼은 태어나기 전에 보아 온 이데아를 되돌아봄으로써 참된 인식에 도달한다고 한다.”고 자세히 설명하고 있다. 쉽게 말해 ‘환기’는 좀 더 느슨하고 추상적이며, 별로 ‘개인적’이지 않다. 반면 ‘상기’는 상당히 구체적인 경험이 개인적인 차원에서 공유되고 있는 상황일 뿐만 아니라 철학적 목표도 분명하다. 이렇게 볼 때 앞서 소개한 ‘메트로폴리탄의 경비원’은 우리에게 다디의 작품을 빌어 ‘환기’하는 바는 있으나 ‘상기’하는 바는 없다고 할 수 있다. 이는 적어도 그 ‘고통 그 자체’라는 부분이 주는 레토릭의 효과가 예술 일반의 속성과 기능에 대해 다 설명할 수는 없다는 결론에 이르게 하는 것이다.

반면 이 전시에서 정직성의 여러 작업을 보면서 경험하게 될 ‘상기’의 효과는 훨씬 개인적이고 피부에 닿는듯한 감각일 것이다. 왜냐하면 그의 작업 면면이 자신의 여러 상황에서 마주한 고통과 번뇌, 즐거운 감정과 실행의 움직임이 갖는 에너지와 극복 의지 등으로 단단하게 엮여 있을 뿐만 아니라 서로 다른 시기에 나온 작업들이라 하더라도 층별로 어떤 어울림을 고려해 그 맥락을 설명해 주고 있기 때문이다. 따라서 감상자들은 설령 작가가 분명히 ‘타인’임에도 불구하고 그 개인이 중층적 삶의 상황과 모티브를 통해 포착하고 재현하며 드러내고자 했던 장면scene을 마치 같은 입장이 된 것처럼 만나게 될 여지가 크다고 할 수 있으며, 적어도 말을 돌리고 돌려서 작업의 가치를 드러내게 하는 현학적 태도가 아니면서도 깊이 있는 감상을 가능하게 한다는 장점이 있다고 하겠다. 이에 대한 이해를 돕기 위해 <미술은 철학의 눈이다>라는 책에 소개된 ‘하이데거의 미술론’은 반 고흐의 <구두>에 대해 “사물과 지성의 일치에 근거한 전통 진리 개념을 거부하고 ‘자기를 열어 밝히는 세계’와 ‘자기 폐쇄적 대지’와의 투쟁에 의해 구성되는 진리의 개념, 일상 세계에서는 경험할 수 없는 도구의 본질이 이중적인 차원에서 제시됨으로써 개별적인 촌 아낙네 구두 회화가 도구의 비목적론적인 가능성을 보여준다. 그리고 이는 앞서서 미래로 기획투사되는 가능성을 의미한다”는 등의 어려운 철학사적 의미로까지 쓰인 현대예술의 도구적 속성으로부터 벗어나게 하는 데 일조한다.

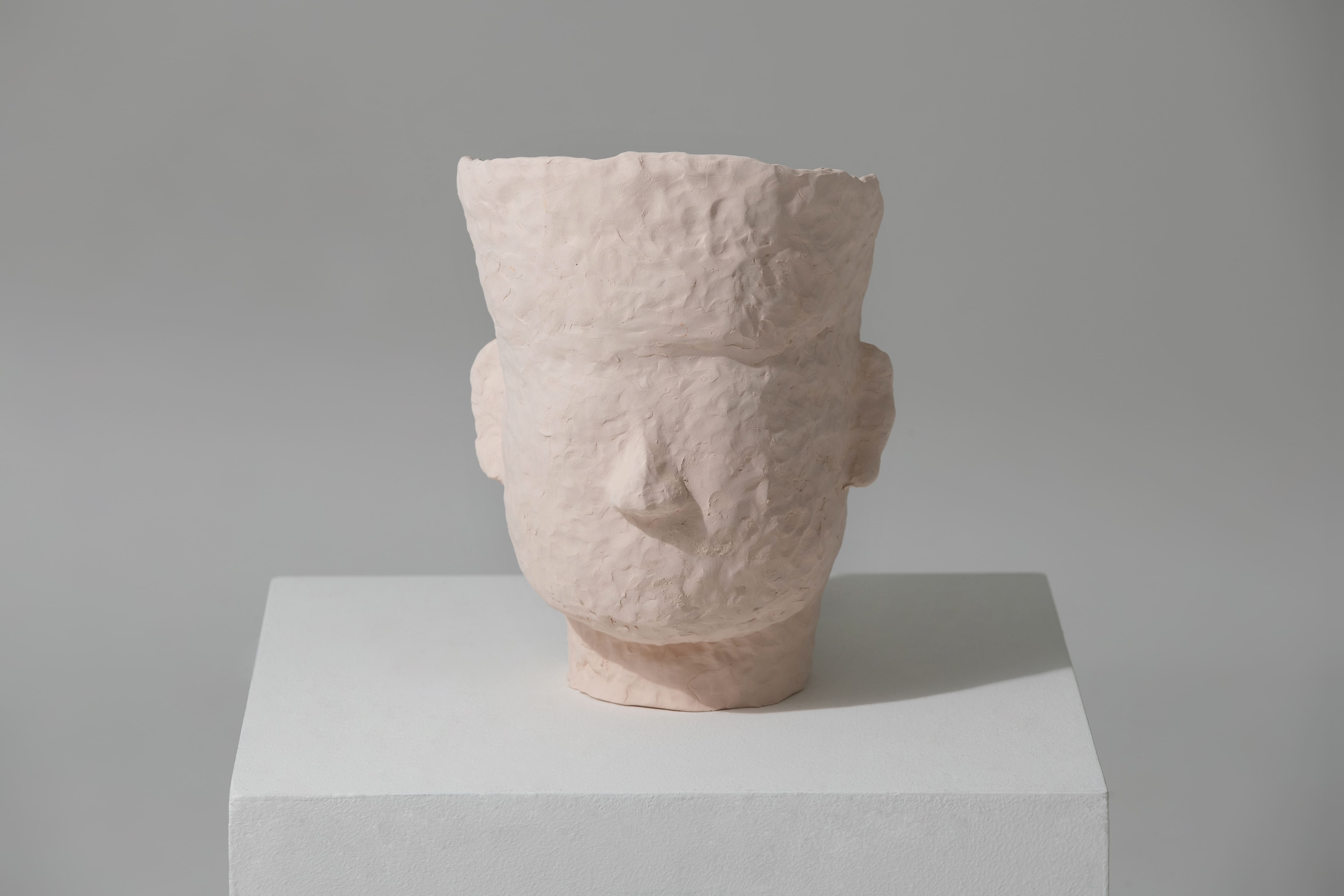

즉, 정직성의 세계는 얼마 전 공개된 유튜브 채널인 오유경TV에서의 타이틀인 “현실을 직시했고, 형식을 거부했다.”이라든지, “현실의 장소 특정적 감각을 추상표현주의적 필법이나 기하학적 추상, 모노크롬 형식 등을 차용하여 표현하는 알레고리적 메타회화 작업” 정도로 충분히 수준 있는 예술에 대한 이해를 돕고 있다고 할 수 있다. 이는 앞의 책처럼 과도한 평론적 시도로 인해 작가의 삶에 대한 관심을 가질 틈도 주지 않는 상황이 아닌, 우리 각 개인이 작가가 환유하는 것을 하나씩 만나가며 작가가 종종 “기존의 의미가 있는 대상들을 가져와서”라고 설명을 시작하는 지점에 대해 관심을 갖고 곱씹어 보는 감상자로서의 지위와 가치를 잃지 않는 것이다. 그러한 점에서 6층의 위트 있으면서도 강렬한 자기소개와 같은 작업들을 만나볼 수 있을 것이다. 이는 문자 추상 작업에서 자신의 경험담을 옮기는 과정에서 서예 선생님이 지도해 준 부분까지 그대로 가져온 사연이나, 어떻게 쓰면 차이가 있고 비장미를 드러내기에 좋은가에 대한 고민, 깨진 해주백자를 붙이고 주전자 작업, 테라코타 작업들, 머리에 대한 그림들과 어우러지게 설치한 작가의 전시에 대한 탐구와 애정을 직관적으로 느낄 수 있을 것이다.

그리고 5층에서는 그간 정직성을 잘 알려온 역동적이면서도 도시적인 상황의 경험을 만나볼 수 있는데, 여기에서는 주요 작품을 모두 보여주기보다는 그것을 구상하는 단계에서 그린 드로잉 등을 더 ‘친절하게’ 공개함으로써 작가 개인의 ‘상기’적 측면을 더 드러냄과 동시에 관람자들에게도 그러한 정서를 돕는 리듬감과 이질적 감정을 공유하는 자리가 될 것으로 기대한다. 나아가 4층에서는 작가가 시각예술가적인 실험을 해나가는 태도를 더 심층적이고 적극적으로 보여준다고 하겠다. 여기에는 특히 정직성의 ‘실험’이 앞서 지적한 누군가들의 ‘전위’에 대한 집착보다는 2013년 현재의 나, 그러니까 금전적 제약 속에서 작은 집으로 이사를 하면서 그 공간을 어떻게 받아들여야 했으며, 어떻게 자신과 작업 환경을 넣어야 하느냐를 고민하면서 자연스럽게 나온 드로잉부터 추상과 구상이 치열하게 부딪치면서 여러 가지 색과 모양으로 시뮬레이션되었던 ‘기록’으로서의 측면도 강해 보인다. 이는 당시 작가의 치열한 고민을 피부로 느낄 수 있음은 물론, 미술사적으로 보았을 때도 마치 아서 단토Arthur C. Danto와 페르니올라Demetrio Paparoni가 ‘현재의 가시성visibility of the present’를 이야기한 기록이 수록된 <예술과 탈역사Art and Post-history>의 “아방가르드와 고전주의 사이에서 ‘삶이라는 친구들’과 ‘형식이라는 친구들’ 사이의 갈등을 소환한다”는 한 대목을 떠올리게 한다. 여기서 그들의 대화가 20세기적 고민을 상기하게 한다면, 정직성의 고민은 그야말로 그때는 예상하지 못했을 21세기적 상황이며, 지금 현재 어떤 개인이 겪고 있는 것이다. 따라서 단토가 예술의 종언을 고하고 역설적으로 개념 미술 위주의 부상을 부추긴 측면이 있음에도 그 ‘멋짐’보다 더 가치 있게 받아들여지는 이유는 “심층 해석은 작가의 의도를 배제한다”며 미래의 예측 불가능성을 이야기했음에 있듯, 정직성의 작업 역시 한국의 미술 역사에서 자신이 어떤 위치에 있는지를 끊임없이 고민하면서 동시에 현실 속에서의 개인 정직성은 어떤 작업을 할 수 있는가를 고민했다는 점에서 오히려 ‘포부’ 보다는 ‘실천’ 자체가 그를 지금의 위치에 데려다주었구나 하는 깨달음을 얻게 한다.

가령 대화의 흐름 속에서 “초현실주의에 대한 분석도 일반적으로, 그러니까 세계적으로 프로이트나 융과 같은 정신분석학에 기대는 도식적 이해가 압도적인 주류이다 보니 한국 현대회화에 대해 잘 맞지 않는 부분들이 있는데 오히려 자본주의의 도입이 주는 충격이 저변에 깔린 것이 아닐까, 그런 해석이 있었다면 더 소화하기 쉽거나 다양해졌을 것”이라는 작가의 의견이 나왔을 때 공감이 간 것이 새삼 ‘정직성답다’고 확인하게 한다. 수월관음도인 ‘관세음란보살’에 대한 설명 또한 유머러스하면서도 자신의 길을 뚜벅뚜벅 걸어가겠다는 결연한 의지를 은연중에 보여주고 있는 것이다. 그렇기에 3층까지 다 내려오면, “지극히 일상적이면서도 세속적인 삶 속에서 이끌어 내는 영성”이라는, 작가가 기본적으로 추구하는 환유의 레토릭에 대해 확실히 느끼게 됨은 물론, 3층이 다시 6층으로 연결되게 하는 묘한 순환 고리처럼 여겨지기도 할 것이다.

그렇다면 왜 정직성은 이러한 환유의 레토릭을 중요시하는 것일까. 이는 아마도 지금의 시대가 ‘삶’이 주체를 환유하지 못하고 주객전도를 시키기 쉬운 속성이 있기 때문으로 보인다. 다시 말해, 우리 각각의 개인은 ‘주체’로서 분명한 인지 능력과 의지를 가지고 하루 하루를 살아가야 하는데, 불가항력적으로 보이는 환경의 여러 요소들에 압도당하는 인생을 살다 보면 ‘내가 본질적으로 어떤 삶에 위치하는가’ 조차 파악할 수 없는 가운데 나이만 먹고 있는 경우가 많다는 것이다. 따라서 나이를 앞세우거나 갈수록 완숙해 간다는 등의 ‘성숙 신화’가 아닌, 초창기부터 직시하고 대응해 온 ‘삶의 고통’에 대해, 자연의 조건과 극복에 대해, 그리고 우리를 지탱하게 하는 가치에 대해 알고자 하는, 또는 알고 있는 이들과의 공명에 대해 일관된 진지함으로 대해오고 그려온 정직성의 세계를 이 정도 규모에서 한 번에 만나보는 것은 지금을 살아가는 우리에게 의미 있는 ‘상기’의 기회가 될 것이다. 그리고 그것은 단토가 말하는 “목적론적 서사가 아닌 자유와 우연의 상호작용에 따른 결과인 탈역사적” 목적도, 하이데거가 말하는 “도구의 비목적론적 가능성”도 아닌, 지금의 상황이 가진 ‘고통 속에서 바라본 비장함과 숭고함’의 재현에 충실하면서, 우리 각 ‘개인’이 어떤 가상적 자아가 아닌 각자의 ‘삶’을 환유할 수 있는 ‘주체’로 느껴질 수 있도록 하는 시각예술가로서의 역할을 해나가는 ‘정직성’의 그 솔직함을 담은 이름값에 대한 기대감이기도 하다.

글/ 배민영(예술평론가)

Layered Life

Forword

From Arouse to Recollect

The Metonym for Jeong Zik Seong’s Life

How is “Honesty” translated in Korean? In his work Honesty=정직성[1], Bach Yi-so re-wrote Billy Joel’s song Honesty and sang it himself, reminding the audience that the word “honesty,” often interpreted as “truthfulness or being true” is most faithfully translated as “Jeongjikseong” in Korean. In particular, in the passage “Honesty is such a lonely word/Honesty is hardly ever heard,” one discovers a sense of tragic beauty that’s sometimes felt in the works by the artist who was inspired by this song and has since been going by the pseudonym Jeong Zik Seong. However, this isn’t completely the same as the “beauty born with emotions like sadness, pain and despair, created in the process where ideal, which should become real, is not actualized in the face of the real” that is commonly taught in literature. This could be a strange ensemble that is produced because it is firmly supported by the sublime beauty in the artist’s work, which is “based on reality yet ideal-directed and thus forms a harmony between real and ideal.”

Beyond the kind of linguistic attributes of her name, the name puts the artist in an advantageous position as it makes us fall into the illusion that there is something in her unique identity shown through her works which goes beyond the “transcendental” realm. The artist might find such popular yet academic aura of her work that constantly invites curiosity and attention rather burdening. However, aways being the sincere and passionate person she is to her own life, the attractive title Layered Life not only appeals to us as a title but also reveals its strong structural persuasiveness as an exhibition that spans across all the four floors of Gallery MEME, from the 3rd to the 6th floor.

Various forms can be used to embellish an artist who has often said that her work “takes meaningful forms from art history and gives them a contemporary meaning.” And these modifiers do not rely on such text but can be conjured up intuitively in the audience. One clear interesting fact is, although it is rare to see a solo exhibition with such a spectrum as this unless it were a retrospective, and it is just as difficult for an artist to be ready enough to do so or process such concepts, Jeong has already shown three large-scale solo exhibitions as grand as this. Now, then, I would like to point out something that audiences in Korea might find frustrating, or is ambivalent to because they are not tolerating it without even themselves knowing. For instance, it would be like being crammed with information through various materials on what relationship lies between Van Gogh’s life and his paintings and then, fascinated by his life, asking ourselves “who would be an artist like that here and now” only to find out that they cannot come up with any. It’s not necessarily correct to assert that it’s because the Korean art world is not as enthralling or lacks information, but what is correctly affirmative is that there are not many exhibitions of such type. In that sense, this exhibition would be a precious opportunity to learn more about the artist Jeong Zik Seong.

Jeong’s world is greatly diverse. She is someone who inhabits multiple layers of time at once that seems impossible for a single person to do, from observation and research to working with her genres and organizing her own exhibitions. Fortunately, Jeong is very articulate in both talking and writing, and she is fully engaged in her expression, seemingly timidly but very proactively, as can be seen in her interviews scattered out the different times and channels online. She has also written several articles and prefaces on her own work. In her essay written for her solo exhibition My Own Words held in Hongseong in November 2020, Jeong wrote: “I have not been able to speak my own words for a long time. As Lacan said, even the unconscious is structured in language. Perhaps it’s because my ineffable sadness and suffering is already structured, but when I try to draw them out through paintings and words, it becomes more painful to see how they would end up as a melodrama that is completely alien to what they were. However, Lee Ungno’s text abstractions brimming with life, which I saw while doing residency at Lee Ungno’s House, seemed to clearly demonstrate that text is just a vessel that contains the mind. As if to say that vessels can be shaped and fired just to serve its purpose to hold the mind, the free liberating text seemed to boldly declare the words.” Such statement helps the reader to better understand the exhibition, and provides a vicariously artistic and emotional experience of the delightful influence of artist residencies on artists. Not only that, but such confession also has an effective element that can largely contribute to understanding the overall context of the artist, by showing such concerns and spatial and temporal context, which is considered very partial among the overall activities. Thus, as this exhibition does not follow a certain chronological order, one might suppose that they start from the 6th floor down for the sake of convenience in the order of movement. The first work the audience would come across, then, would show a sense of the unshakable and unambiguous level of self expression that Jeong pursues, indisputably evident throughout the diversity of her works. At times her work would try to be too radical, then lose balance and ironically lose its identity. At other times, it would seem to show just one facet, so that, although the work is excellent and not dull, it would indirectly share her identity as a Korean while not focusing on ethnicity. Lastly, Jeong’s work traverses across various genres yet each one of them demonstrates a high level of perfection. In short, they are qualities that turn her audience into her “fan.”

What is most important is that Jeong’s work goes beyond the dichotomy of abstract and representational, to having a sense of “being here,” which can unveil even “symbols implying smell and memories” as expressed by the artist. And because it does so, the work has what the artist calls the “assurance that there is a sense of universality that is able to resonate with others” and this is actually being represented in her paintings and other forms. This presents new possibilities for the so-called “typicality” and keenly plays the role of taking the function to “arouse,” which is generally regarded as a virtue of art, to the sphere of “recollecting.”

Rather than bringing up texts by any critics, I would like to take a moment to focus on a book written by an ordinary person and an art lover, living today. All the Beauty in the World by Patrick Bringley captures his 10 years of experiences as a guard at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in a clear, realistic, and in-depth narrative. He wrote that Bernardo Daddi’s The Crucifixion is the “saddest painting in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art” and that “while painting was suffering for Daddi, it must have been a much-needed tool that enabled him to carry out his thoughts.” He demonstrated his perspective as a writer, saying that “Daddi painted suffering itself. Great art seems to remind us about obvious facts. All it does is tell us that ‘this is reality.’ I’m not sure if I’m understanding the actual fears produced through the suffering of this moment in a way that is as clear as Daddi’s great works, but we end up forgetting that fact soon. We gradually lose such clarity. As if to repetitively look at the same painting, we must confront that reality again.” It's a wonderfully insightful passage. But what strikes us as we read such text, is that despite so, we feel a sense of distance or superficiality. This is not a story of whether one has faith or not, or a sense of gap a person from the East feels when looking at a work from the West. This is a story about the very distance of the impact that a work has on an individual’s psychology. In that case, it is imperative to discuss the two words, “arouse” and “recollect,” which are used almost without distinction but are essentially different. In dictionary, “arouse” is simply defined as “to cause someone to have a particular feeling or thought.” On the other hand, “recollect” is explained in a lengthy detail: “to recall to mind; recover knowledge of by memory; remember.” In Plato’s term, it’s the process through which the human spirit gains the true knowledge of idea. The human soul becomes a true human being by recalling such innate ideas. In other words, “arouse” is more vague, abstract, and not very “personal” while “recollect” describes how quite a specific experience is shared on a personal level, backed with a clear philosophical idea. In that sense, the abovementioned guard at the Metropolitan Museum of Art “arouses” us through Daddi’s work, but does not lead us to “recollect” anything. And this leads to the conclusion that the effects of the rhetoric in the "pain itself" cannot fully explain the properties and functions of art in general.

Meanwhile, the effect of “arousal” one will experience through Jeong’s numerous works in this exhibition will be in a much more personal and closer to a skin-like sensation. This is because aspects of her work are tightly intertwined with the pain and anguish the artist has faced in various situations, as well as pleasant emotions, the energy to overcome in the movement of her actions. Not only that, but even if the works are all from different times, they are explained in their environment, within the context of each floor. Therefore, it is highly probable that the audiences would be able to experience Jeong’s works—the scenes where an individual attempted to capture, represent and expose through conditions and motives of layered life—as if they were in the same position as the artist even if the artist is clearly an “other.” This means that Jeong’s work, at least, has the strength of allowing a deep reading of her work, without being pedantic and boasting off its value through ambiguous words. Heidegger’s theory in the book Art is the Eye of Philosophy helps to explain this point. It talks about Van Gogh’s painting A Pair of Shoes, which rejects the traditional truth concept that is based on the agreement between matter and intellect, and supports one that is formed through the confrontation between “a world where one is open” and “a land that confines the self.” The painting of a country woman’s shoes demonstrates the non-objective potential of the tool, by proposing the essence of tools, which cannot be experienced in everyday life, in a twofold dimension. And this signifies the abovementioned possibility of Entwurf. Jeong’s work helps to take off from the instrumental attributes of contemporary art that is grounded by such difficult philosophical meaning.

In other words, the world of Jeong Zik Seong helps us to understand high quality art, as can be seen in examples like “Looking at reality, Reject Form,” the title of the recently-released YouTube Channel Oh Yookyoung TV which features the artist, or as “allegorical meta painting that expresses the site-specific senses of reality, borrowing styles such as abstract expressionism, geometric abstraction or monochrome form.” Unlike the abovementioned book where excessive critical attempts take away the space in which to focus on the life of the artist, it’s about each one of us maintaining our status and value as the audience of her work, touching one by one everything the artist presents as a metonym, and paying attention to the points where the artist sometimes explains as “meaningful subjects summoned from the past.” In that sense, the works on the 6th floor seem to be a powerful and witty introduction to the artist herself. Here, the viewer can instinctively feel the artist’s exploration and affection for her exhibition, in the artist’s telling of her experiences of the calligraphy teacher who helped her in her text abstract works, her thoughts on how it should be written to show distinction and demonstrate a sense of tragic beauty, and how she put together a broken Haeju baekja and installed it in context with her kettle works, terracotta works, and head paintings.

On the 5th floor, the audience comes face to face with dynamic urban elements in Jeong’s works, for which the artist is acclaimed. Rather than showing all the major works, the artist sheds light on the drawings she created in the making process of such works in a more “friendly” way, emphasizing the element of “recollecting” in the artist’s works while sharing with the audience the rhythm to experience such gestures along with other different emotions. Then on the 4th floor, the works demonstrate a deeper and fuller view on Jeong’s outlook on her visual art experiments. Rather than obsessing over the “avant-garde” mentioned above, Jeong’s “experiments” range from her drawings as a natural outcome of the artist’s everyday concerns about her very own life in the present in 2013—such as thinking about ways of dealing with her work and practice in a small space in a small house she had to move into due to financial tightness—to her “records” that simulate various colors and forms as a result of intense clash of the abstract and representational.

Not only do we actually feel the artist’s intense concerns at the time, but also in terms of art history, it brings to mind a passage from Art and Post-history which contains records of Arthur C. Danto and Demetrio Paparoni’s conversation on “visibility of the present,” in which “the conflict between “friends of life” and “friends of form” in between avant-garde and classicism is recalled.” While their conversation here touches upon 20th century subjects, Jeong’s issues concern the 21st century which wouldn’t have been a subject of discussion in Danto and Paparoni’s time. They are issues that an individual in the present is experiencing. While Danto informed the death of art which paradoxically incited the emergence of conceptual art, Jeong’s issues are embraced with more value because the future is unpredictable and “deep analysis leaves out the artist’s intentions” as explained by the artist. Jeong’s work also relentlessly ruminates over where her work situates in the history of Korean art while contemplating what her art can be in the contemporary reality. In this sense, we come to the realization that it was through “practice” over “aspirations” that Jeong is where she is today.

Jeong once said in a conversation, “Analysis of surrealism in general, or universally, is dominated by a schematic understanding that relies on Freudian or Jungian psychoanalysis, so there are parts that conflict with Korean contemporary painting. If the analysis took in consideration the shock of Capitalism as its basis, it would be more diversified and easier to take in.” Such opinion, so much like Jeong herself, strikes a chord deep within.

The artist’s explanation about Paintings of Water-moon Avalakiteshvara is humorous while implicitly demonstrating a determined will of the artist to walk her own way. By the time the audience reaches the 3rd floor, not only would they have clearly witnessed the rhetoric of metonym the artist pursues, or the sense of “spirituality drawn from a completely ordinary yet secular life,” but also experience a bizarre loop where the 3rd floor connects with the 6th floor again.

So why is such rhetoric of metonymy this important for Jeong? Possibly because in this day and age, “life” cannot be a metaphor for the self as the subject and can easily reverse the order. In other words, while we should be living day to day with a clear sense of consciousness and will as the “subject” of our own lives, we find ourselves just getting older, overwhelmed by various seemingly inevitable environments, and not being able to even grasp “essentially what kind of life” we are living. Therefore, rather than the “myth of maturity” that believes in age and maturity as a course of time, it might be a more meaningful opportunity of “recollecting” for us today, to meet Jeong in such large-scale exhibition, and her works that have always explored, in a consistently serious and sincere manner, the “suffering of life” since the onset, conditions of nature and overcoming it, and resonance with those who know or wish to know the values that sustain us. And this does not reflect the “post-historical purpose as a result of interaction between freedom and coincidence as opposed to teleological narrative” as coined by Danto, nor Heidegger’s “non-teleological potential of the tool.” Rather, Jeong fulfills her mission as a visual artist who, while remaining faithful to the representation of “resoluteness and loftiness seen from the midst of suffering” in the present, invites each “individual” to recognize him or herself as a “subject” to draw the metonym of their own “life” and not some imaginary ego. That is why we have high expectations in this artist with such a genuine name: Jeong Zik Seong.

Text by Bae Minyoung (Art Critic)

[1] 정직성 (pronounced Jeongjikseong) means “honesty” in English and is also the name of the artist (Jeong Zik Seong) in this exhibition.